The Insights You

Need

are Right Here

VISASQ/COLEMAN was established in 2021

as a partnership between

Asia’s top expert

network firm, VisasQ Inc. and Coleman

Research, a trusted

expert service provider

with more than 20 years of global

experience.

What We Do

Our goal is to provide global leaders and business investors with the expertise needed to make better decisions.

There are barriers to knowledge and our mission is to remove them – with a global platform for the direct and rapid exchange of critical insights.

Why Our Clients Choose

VISASQ/COLEMAN

Precise Custom

Recruitment

Targeted custom recruitment is a fundamental element of our service. Approximately 20% of our experts on any given projects are custom sourced.

Unique

Network

A dynamic and expanding network of global thought-leaders and experts, hand-selected for over 20 years, with exceptional depth in Japan and the United States.

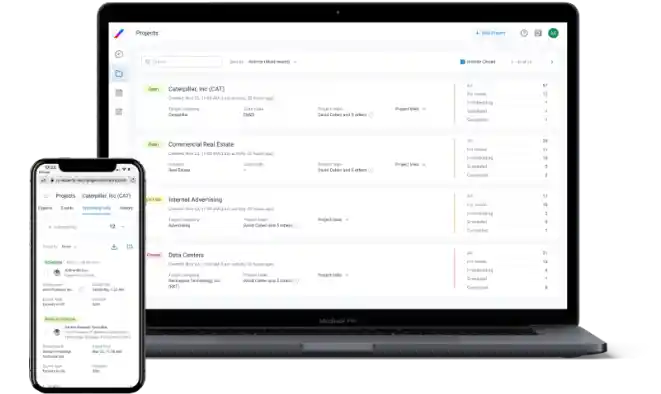

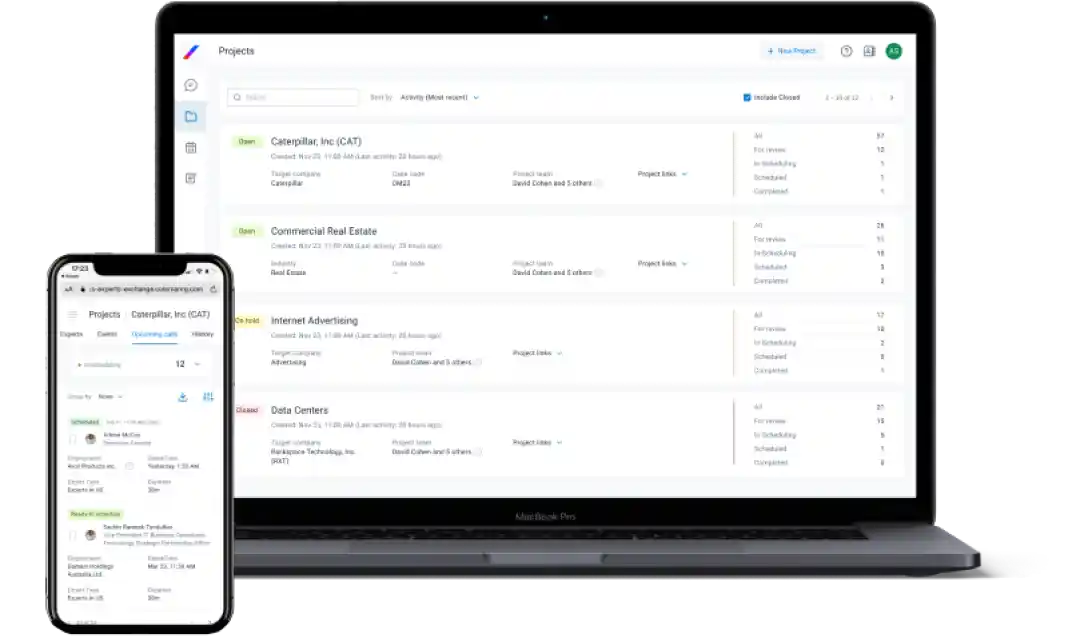

Industry-Leading

Client App

A clear and simple UI enables straightforward project submission, while our UX supports instant expert reviews, as well as consultation scheduling and hosting.

Rapid Expert

Scheduling

7 offices across the US, EMEA, and APAC working 24/5. Average custom recruiting time is less than 24 hours. In-network experts can be scheduled in less than an hour.

Robust Compliance

Framework

A fully customizable platform makes firm-specific compliance protocols easy to implement and manage. Utilization and interactions can be easily reviewed via our Compliance App.

How We Work

Our teams work hard to understand your investment and research objectives, so we can provide you with the tools and services to quickly connect you to the right experts.

Bespoke online or in-person consultations with a qualified VISASQ/COLEMAN expert for in-depth insights.

- Idea generation

- Channel checks

- Broaden industry knowledge

- Qualitative verification of hypotheses

Mini-surveys, quickly administered, provide fast answers to questions from multiple experts.

-

Quick, quantitative verification of hypothesis (possibly before or

after 1:1 calls) - Initial market/industry research

Customizable questionnaires that can be shared with VISASQ/COLEMAN experts to deliver accurate data you can trust.

- Broader, quantitative verification of hypotheses (possibly before or after 1-on-1 Consultations)

- Transcripts

- Additional Research

- Moderated Calls

- Deal Placements

Case Studies

Learn how companies around the globe use VisasQ/Coleman to get the relevant insights they need to make better business decisions.

US Private Equity Firm Researching new Wireless Communications Company in Asia

Targeted Research Enables Hedge Fund to Uncover Advertising Trends in Social Media Industry

Major U.S. Corporation Partners with VISASQ/COLEMAN to Survey Experts Outside of Its Internal Network